2025-01-04

The Safeguard Mechanism provides little more than a fig leaf of respectability to Australia’s efforts to tackle global warming

By Mark Brogan

On October 15, WA's Environment and Climate Change Minister, Reece Whitby, announced plans to strip the State's environmental watchdog, the EPA, of the power to assess Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG-e) from big polluting projects. Henceforth, projects in WA with an estimated annual output of 100,000 tonnes or more of CO2-e would have their emissions assessed under the Commonwealth Government's so-called Safeguard Mechanism (SM).[2] The SM is administered by the Commonwealth as a core component of its emissions reduction programs. [3]

In explaining the reform, Whitby argued that a State approval process amounted to needless 'duplication' of the existing Commonwealth process under the SM. The move made Western Australia the first and only state to have spat the dummy on regulation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG-e). But this was not the first time that WA Labor has drawn from the neo-liberal well of resistance to regulation. The Cook and McGowan governments have a record of citing 'red tape', 'green tape' and 'duplication' as justifications for eroding or removing regulations that are unpopular with their industry sponsors or found to be politically unpalatable for some other reason.

They have not acted in isolation. A sympathetic ear has been lent by the Albanese Government which increasingly sees its electoral prospects as depending on keeping the west on side. Concurrently, it is also seeking to pass new environmental legislation, that will include no

GHG-e emissions power of review. [4] Instead, you guessed it, projects will be assessed under the SM.

Since its inception almost a decade ago, the SM has gone from obscurity to centre stage in Australia's emissions reductions effort. So what exactly is the SM? With so much of Australia’s and the world’s emissions future invested in it, will it function as Whitby and Plibersek claim to reduce carbon emissions from our biggest polluters?

The Safeguard Mechanism: From obscurity to centre stage

The Safeguard Mechanism began life as a little known and little commented upon Abbott era reform following the dismantling of the Gillard Government's Carbon Pricing Mechanism in June 2014. The SM commenced officially under the Turnbull Government in 2016. [5] Along with an Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) that paid big polluters to reduce emissions, the SM prescribed baseline emissions for high polluting Australian facilities. Facilities that exceeded agreed baselines were required to either:

- acquire and surrender Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs)

- apply for a multi-year monitoring period (MYMP) to allow more time (up to 3 years) to purchase ACCUs or reduce emissions. [6]

Baselines were calculated with an eye to a weak emissions reduction target agreed as part of the Turnbull Government’s commitment to the Paris Agreement in 2016, i.e. a 26-28% reduction on 2005 levels by 2030. Since Australia calculates emissions inclusive of Land Use, Land Use Changes and Forestry (LULUCF), this weak target was to be calculated nett of land use that sequestered emissions. More on this later.

The Period 2016-2022

Following its formal establishment, limitations of the SM as a means of reducing Australia's emissions soon became apparent. During the first five years of operation between 2016 and 2021, emissions covered by the SM increased by 4.3 per cent. [7] The SM was enabling emissions growth. Effectiveness of the early scheme was undermined by issues with scope, flexible baselines, and a flawed overarching policy framework.

The Scheme initially covered only one hundred and forty (140) facilities each emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of Carbon Dioxide Equivalent (CO2-e) in a year. [8] Companies could request a re-calculation of a facility’s baseline, providing for the expansion of emissions over the productive life of plant, if required. [9] The agency responsible for administering the scheme, the Clean Energy Regulator, lent a very sympathetic ear. A 2018 investigation by consultants Reputex found that the agency had authorised 57 facilities covered by the mechanism to expand emissions above agreed baselines. Further, Reputex estimated that emissions at the newly approved levels could add 22m tonnes of CO2-e into the atmosphere each year representing 4% of Australia’s annual emissions.[10] Emissions expansion had diminished the value and impacts of $2.25bn worth of abatement purchased by Clean Energy Regulator via the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF).

The SM initially operated within the policy framework of the Coalition’s so-called Direct-Action Plan. Introduced in July 2014, the plan passed pollution abatement costs to the Australian taxpayer via an Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF). The plan worked by providing funding to companies to incentivise emission reduction activities. The government spent A$1.7 billion on 143 million tonnes of emissions, at an average cost of A$12 a tonne in its first year of operation.[11] The premise that Government would pay for emissions abatement flew in the face of conventional economic wisdom, namely, that for effective reductions, the polluter should be required to pay furnishing a disincentive to pollute. It was also unsustainable as a tool to bring down emissions because of its budgetary implications. Although the scheme in principle could insist on the purchase of offsets (i.e. ACCUs), coalition governments were ideologically committed to neither genuine emissions reduction nor imposing cost burdens on Australian business.

Maligned initially by the Abbott Government and then by its coalition successors, emissions abatement policy in the long run has reverted to an idea first envisaged by the Rudd Government in 2009 and enacted initially in limited form by the Gillard Government in 2011. Emissions above agreed baselines or for new large polluting facilities should be offset by the purchase of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs), i.e. tradeable financial units that monetize emissions avoided or sequestered.

The opportunity to make money from offsets in one of the world’s most carbon intensive economies per capita has since proved irresistible. Since introduction of the ACCU scheme in 2011, 137 million ACCUs have been issued. [12]

The Reform of the Safeguard Mechanism in 2023

In the context of weak national emissions ambition, failures of the Safeguard Mechanism attracted little attention. However, with the election of the Albanese Labor Government in May 2022, a more ambitious (but still weak) emissions reduction goal of 43% on 2005 by 2030 was enshrined in the Climate Change Act 2022. [13] This more ambitious target made review of the operation of the SM a priority.

In 2023 the Safeguard Mechanism was overhauled. Revisions to the SM have taken place against a backdrop of rising concern about the integrity of ACCUs. In 2021, The Australia Institute found that offsets for avoided deforestation did not meet integrity standards. [14] In another 2023 study, researchers Macintosh and Dunn reported that three quarters of ACCUs issued came from avoided deforestation in NSW, combustion of methane from landfills or human-induced regeneration of native forests in arid areas of inland Australia. [15] Macintosh and Dunn likewise blasted the scheme for a lack in integrity:

People are getting carbon credits for not clearing forests that were never going to be cleared anyway, for growing trees that already exist, for growing forests in places that will never sustain them, and for operating electricity generators at landfills that would have operated anyway. [16]

While substantially denying most integrity allegations levelled against the scheme, the Albanese Government nonetheless implemented major changes to the Scheme from 1 July 2023. [17]

Features of the revised SM included:

- An expansion of the number of facilities covered to 215 accounting for 28% of Australia’s emissions;

- Baselines that are expected to decline by 4.9% each year;

- Safeguard Mechanism credit units (SMCs) to incentivise facilities to operate below their baselines

- More options for managing excess emissions. [18]

In summary, the SM has moved from obscurity to centre stage in emissions reductions. In 2024, it has been 'beefed up' with changes that align with a more ambitious overall emissions reduction target (43% by 2030). So is the SM now fit for purpose?

There and back again: Fitness for purpose of the revised Safeguard Mechanism

Limitation of Scope

The SM is a scheme to set baselines and reduce emissions from Australia’s largest emissions emitters with annual production related emissions above 100Kt CO2-e. These are so-called Scope 1 emissions i.e. emissions owned or controlled by a company operating out of an Australian facility producing at or above the required threshold for inclusion. The SM does not apply to Scope 2 & 3 indirect emissions, i.e. emissions that are a consequence of the activities of the company but occur from sources not owned or controlled by it. The downstream consumption of Australia’s fossil fuel exports to produce emissions is an example of Scope 3 emissions. Australia is a major contributor to global warming and climate change via Scope 3 emissions. Most arise from the consumption of fossil fuels in foreign markets, mainly Asia and South Asia. These emissions far outweigh and dwarf the Scope 1 domestic emissions produced by facilities covered by the SM.

The quantum of difference and its environmental consequences are best seen by example. Woodside’s Northwest Shelf (NWS) license extension proposal, which seeks approval to extend North West Shelf project’s operating license out to 2070, involves Scope 1 emissions within the range of 128.2 Mt CO2-e to 385 Mt CO2-e. [19] Scope 3 emissions on the other hand, are expected at around 4Gt CO2-e i.e. 4 billion tonnes or 91% of total CO2-e. [20] Scope 3 emissions therefore dwarf Scope 1, but are out of scope as far as the SM is concerned. The story is repeated elsewhere with other LNG projects.

The Australia Institute estimates that Tamboran Energy’s Beetaloo Project’s Scope 1 lifetime emissions at 420 Mt CO2-e. [21] Exported (Scope 3) emissions are estimated at 1.2 Gt CO2-e over the project’s lifetime.[22] According to Climate Analytics, emissions could be much greater with Beetaloo and could range up to 3.2 Gt CO2-e combined. [23] At the upper threshold, these two projects combined represent 3% of our remaining global carbon budget for remaining within the 1.5°C global warming threshold. The WA Government currently has 21 gas projects in various stages of the approval process. [24] Ouch.

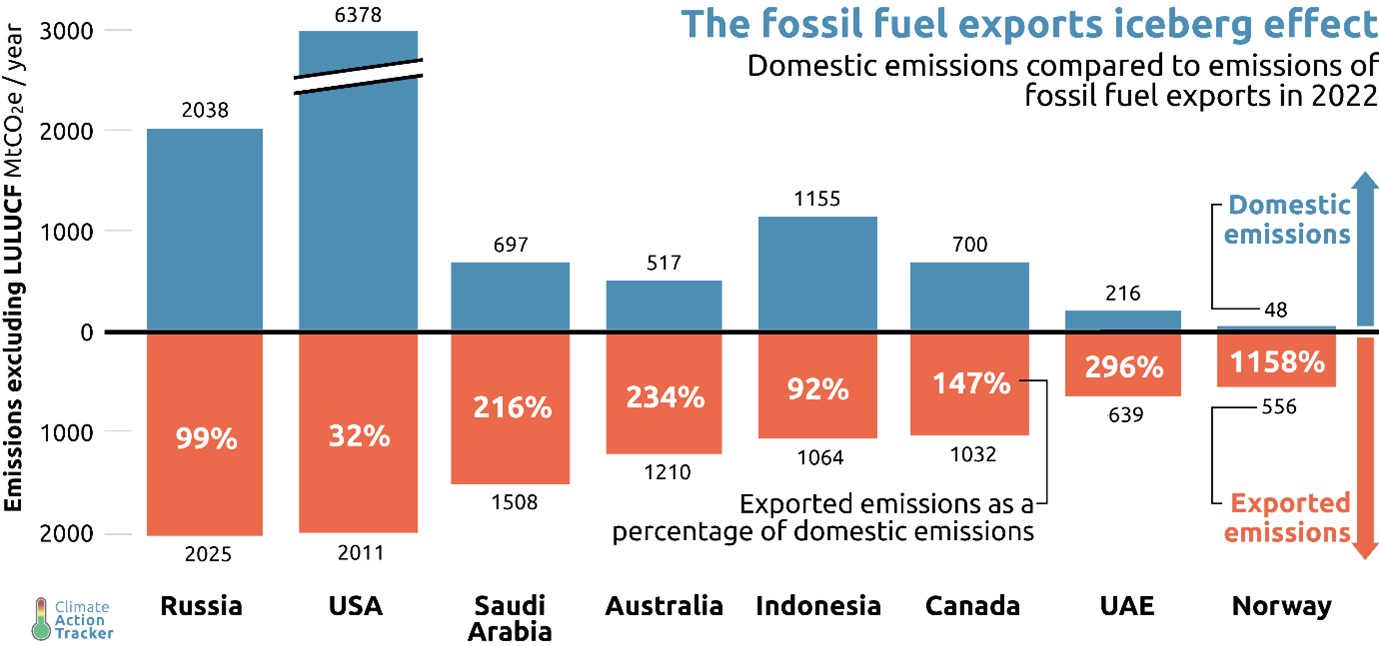

The wicked problem of Scope 3 exported emissions coming from Australia’s fossil fuel exports is shown in Figure 1:

Australia’s exported emissions are 234% of domestic emissions. Putting it differently, exported emissions account for 70% of all emissions from Australian fossil fuels. [25] According to industry analysts, Climate Analytics, Australia’s exported emissions have increased by 40% between 2010 and 2022.[26]

In summary, the SM excludes Scope 3 exported emissions which are Australia’s main contribution to the problem of global warming. Each new gas or coal project approved is a nail in the coffin of limiting the effects of climate change to the manageable Paris Agreement threshold of 1.5°C. Nothing in the current architecture of the SM mitigates exported emissions.

Junk Bonds? Offsets and ACCUs

There are other architectural issues with the SM. Importantly, according to some opponents, the availability of offsets has the potential to blow out of the water Australia’s current modest goal of 43% emissions reduction on 2005 by 2030. [27]

Fossil fuel carbon pollution is hard to abate by avoidance. The idea that emissions growth can be offset by sequestration of carbon via ACCUs is a foundation architectural principle embedded into the SM. The idea’s origins are to be found in the approach taken by the Howard Government to the Kyoto Protocol, where the Australian Government insisted on a method of GHG-e accounting inclusive of sequestration via Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (so-called LULUCF). This form of carbon accounting was a concession made to Australia to bring it on board with Kyoto Protocol. In practice, LULUCF has worked to mask GHG-e expansion in Australia. The chart below (Figure 2) is taken from the Albanese Government’s 2023 Annual Climate Change Statement. [28] It describes emissions by type and inclusive of LULUCF:

The impact of LULUCF on nett total emissions (the dotted line) is clearly seen with negative emissions attributed to LULUCF from 2015. Relative to the baseline year, LULUCF delivers a downward trend in nett emissions. Excluding LULUCF the picture is different. The following graph (Figure 3) shows annualized CO2-e emissions data excluding LULUCF for the period 1989-2022.[29]

Review of the data by sector shows that stationary energy, a sector that includes coal and LNG, and transport are the most significant drivers of emissions growth. Stationary energy pollution has grown by 22% since 2005, mainly due to pollution from an expanding LNG and coal export industry. [30]. Transport has grown by 20%. Combined emissions from stationary energy, transport, fugitives, industrial processes and product use are expected to be 10% higher than 2005 in 2030. [31]

Since the SM is intended to explicitly address growth in emissions from stationary energy including LNG and coal, we conclude that with current trends and further coal and gas projects in the pipeline, the SM cannot address emissions growth through avoided emissions. In Western Australia, there are currently 21 in process or approved safeguard projects according to the EPA with cumulative domestic (Scope 1 & 2) emissions out to 2050 of 306 Mt CO2-e [32]. These and other emissions for safeguard projects in other States will need to be abated via ACCUs and these will need to be available at sufficient volume, quality and diversity to enable genuine emissions reduction. As its critics argue, herein dwells a ticking time bomb for the SM. ACCUs are unlikely to be available at the required, volume, quality or diversity to meet the requirements of abatement in the context of rapid pollution expansion from new carbon polluting projects. The evidence is clear.

A performance audit by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in 2024 found that as of January 2024, 1,769 projects had been registered against 52 ACCU methods. ACCUs have been issued to 633 projects using 36 ACCU methods. Of the more than 140 million ACCUs current at the time, 77 million (55%) had been issued for vegetation and sequestration. A further 43 million had been issued for landfill and waste treatments (30%) with all other methods accounting for only 15% of ACCUs issued. [33]

The ACCU system is over reliant on two methods of abatement with vegetation and sequestration accounting for more than half of all ACCUs. Failures in the system for managing this method of abatement had been the subject of allegations in 2022. In his review of the ACCU system, Professor MacIntosh, a former head of the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee, claimed that failures in the ACCU system meant that 70% of carbon credits approved might not represent new or real cuts in emissions. [34]

Even if problems of quantity and quality could be overcome with the ACCU system, there are other issues with offsets. In reality, the ACCU system is a form of static analysis that cannot guarantee that abatement will be permanent. Nor can it isolate abatement from feedback in the climate system that makes abatement vulnerable. For example, it makes no allowance for the feedback consequences of already significant climate change or the long-lasting warming effects of GHG-e in the atmosphere. In 2022, Europe saw record-breaking temperatures during summer and autumn, with 30% of the European continent experiencing severe drought. Research showed that the extreme conditions lead to a reduced net biospheric carbon uptake in summer (56-62 TgC) over the drought area. This reduction of uptake was more than the yearly emissions of the country of the Netherlands and about 80% of the total yearly emissions of France. [35]

As Australia’s climate dries and drought frequency and intensity increases, the sequestration capacity of our forests, grasslands and soils will diminish as they did in Europe in 2022. Sinks also have the potential to be destroyed by bush fires. The loss of sequestered carbon from large uncontained bush fires can approximate whole of life cycle Scope 3 emissions from LNG projects or total annual emissions. For example, the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-2020 are thought to have been responsible for 715 Mt CO2-e, more than 1.5 times greater than the total reported emissions for all other sectors. [36] Offsets also function as a multiplier on carbon pollution since domestic offsets are enablers of exported carbon pollution. Considering the case of LNG, according to Climate Analytics, each offset tonne of production emissions (Scope 1), enables eight tonnes of exported (Scope 3) emissions as gas is burnt in overseas markets. [37]

A war of numbers

Integrity in accounting relies on trusted numbers. If caps such as baselines are to be meaningful, measurement of emissions needs to be trustworthy and reliable. But increasingly, we find numbers describing emissions (or abatement) in dispute.

In 2023, the International Energy Agency (IEA) revealed that methane emissions from Australian coalmines and gas production, could be 60% higher than Federal Government estimates. [38] Earlier in 2021, remote sensing using satellite imagery, cast doubts about the reliability of company reported emissions from coal mines in the Bowen basin in Queensland. Geospatial analytics firm Kayrros found that Federal Government estimates reported only one third of actual emissions. [39]

Numbers with new projects are also increasingly contested. The Northern Territory’s Beetaloo Basin is a case study. In its Scientific Inquiry into Hydraulic Fracturing of Onshore Unconventional Gas, the NT Government relied upon CSIRO/GISERA estimates of GHG-e. GISERA is a gas research arm of CSIRO that aims to “to inform governments, policy makers, industry and communities of key research outcomes around the environmental and socio-economic impacts of the gas industry.” [40] GISERA receives thirty per cent (30%) of its funding from the gas industry with the remaining seventy per cent (70%) provided by CSIRO and Australian Governments. [41] Independent Analysts, Climate Analytics, found that the GISERA estimates:

Underestimated emissions for the Beetaloo project and its associated LNG production facilities across the board, across all areas of the proposed project, from methane leakage on extraction to liquefaction emissions intensity.[42]

Further that:

these emissions would add up to 11% of Australia's 2021 emissions, and that: the methane loss rate is underestimated by at least 56%; the upstream emissions intensity is underestimated by 44% to 110%; and, LNG production emissions underestimated by 57% to 89%.[43]

The Australian Government plays its own numbers game. Armed with its Kyoto concessions on land use and forestry (LULUCF), it prefers the reporting of emissions as part of its national inventory inclusive of LULUCF. Goal setting, including the 2030 target of 43% below 2005, is also inclusive of LULUCF. [44] As we have seen, uncertainty about abatement savings from LULUCF inclusive of issues of permanency, volume and quality of offsets is well represented in the literature on emissions mitigation. The reporting of emissions therefore exclusively inclusive of LULUCF, without discussion of raw emissions trends (i.e. minus LULUCF) omits critical information necessary to understanding emissions trends and their implications.

With increasing public awareness of emissions reduction estimates having been distorted by suspect accounting practices, the Australian Government has adapted to criticism from the Australia Institute [45] and others by removing figures and discussion of emissions minus LULUCF in its reporting. Most commentary on numbers carries no qualifications about methodology and uses new terminology, namely ‘historic emissions’. On the back of a small reduction in annual emissions in 2024 of 2.9 million tonnes (Mt CO2‑e) and trend analysis of ‘historic emissions’, Climate Change Minister, Chris Bowen, has claimed that Australia is on track to achieve its goal of a reduction of in ‘gross’ emissions of 43% or better by 2030. [46] Annualized emissions to 30 June 2024 were reported at 440.6 Mt CO2-e down 28.2% on the 2005 baseline, providing assurance according to the Minister that emissions are indeed tracking to secure the 2030 goal of 43%.[47]

So what exactly is the situation when the standard of raw emissions is used in place of nett emissions (i.e. emissions minus LULUCF)? The data can be extracted from the Excel inventory data for our national GHG accounts. [48] When this is done the progress against the 2005 baseline as of 2024 is only 14%, effectively half the reduction claimed inclusive of LULUCF. Sectoral data in these accounts shows that to the extent that this modest aggregate reduction has been achieved it is on the back of the electricity sector (-22.4%), agriculture (-4.8%) and waste (-11.5%). Stationary energy (Gas and coal) increased (+20.8%) along with transport (+20.1%), fugitive emissions (+11.7%) and Industrial processes (+6.7%). [49]

Conclusion

In summary, we conclude that the bark of Australia’s watch dog on emissions is worse than it’s bite and that by virtue of design and implementation flaws involving scope, offsets and accounting, the SM is enabling the growth of Australia’s emissions problem.

The Safeguard Mechanism did not have an auspicious beginning tracing its origins to the Abbott Government's hatchet job on the Gillard Government's Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS). The history of operation of the scheme is vexed involving concessions to polluters, dubious accounting and contested science around offsets and the calculation of emissions. Even if these issues could be fixed, the damage being done to the world’s and our own ecosystems by Australian sourced carbon pollution will continue to grow, as more coal and gas is exported and consumed in offshore markets. This destruction is the result of the emissions pipeline known as Scope 3 emissions. With variations from project to project, Scope 3 emissions account for between 70% and 90% of emissions from Australian fossil fuels. It is primarily these emissions that are destroying our coral reefs, acidifying our oceans, causing biodiversity loss, extreme weather events and threatening our very existence.

In the absence of a climate trigger that can be used to stop big polluting gas projects, the SM provides little more than a fig leaf of respectability to Australia’s efforts to tackle global warming. Reviewing operation of the SM since 2016, we can see its evolution and operation being shaped by bi-partisan consensus not to get in the way of Australia's fossil fuel industries. The SM does not deal with Scope 3 emissions and provides no test of pollution against the Paris Agreement remaining budget for 1.5 C. Whitby’s deal with the Albanese Government to end EPA’s role in assessing GHG-e with new fossil fuel projects in WA, and Albanese’s deferral of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Bill, are just the latest chapters in this unfolding story of capture, hypocrisy and political expediency.

Greens and Independent attempts to secure a climate trigger to stop big polluting projects from getting off the ground have been frustrated. Currently, the SM Act requires the Climate Change Minister to assess new or expanded projects against the Act. [50] However, this requires the reporting of Scope 1 and 2 emissions to the Federal Environment Minister. This and other reforms for a working trigger were to be included in the new Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. As a result of intervention by the Cook Government, the EPBC has been stalled and will not be revisited before the WA state election. With as yet no new architectural elements in the regulatory framework that require assessment of the 70% or more of Australia’s emissions that come from the burning of Australian coal and gas abroad, work on constraining Australia’s contribution to global warming remains necessarily incomplete. This is the emissions elephant in the room that our SM watchdog in its current form is powerless to address.

References

[1] This article is dedicated to the memory of Paul Patak a former colleague and friend who cared about nature.

[2] Hastie, H. (2024). WA’s environment watchdog stripped of power to assess big polluting projects. WAToday , 15 October 2024. Retrieved from:- https://www.watoday.com.au/politics/western-australia/wa-s-environment-…

[3] ibid

[4] Middleton, K. and Cox, L. (2024). Labor's stalled environmental agenda under pressure from left and right. The Guardian. 13 September 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/sep/13/labor-stalled-en…

[5] Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, and Environment and Water. (2024). The Safeguard Mechanism: About the Safeguard Mechanism and the reforms. Retrieved from: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/safeguard-mecha…

[6] Australian Government. Clean Energy Regulator. Safeguard Mechanism before 1 July 2023. Retrieved from: https://cer.gov.au/schemes/safeguard-mechanism/safeguard-mechanism-1-ju…

[7] Carbon Market Institute. (2024). Safeguard Mechanism: Historical Context and FAQs. Retrieved from https://carbonmarketinstitute.org/app/uploads/2023/01/Safeguard-Mechani…

[8] By November 2023, the number of facilities covered had grown to 220. Vide MacIntosh, A. and Butler, D. (2023). The unsafe Safeguard Mechanism: how carbon credits could blow up Australia's main climate policy. The Conversation. Retrieved from:- https://theconversation.com/the-unsafe-safeguard-mechanism-how-carbon-credits-could-blow-up-australias-main-climate-policy-213874

[9] Carbon Market Institute. (2024). Safeguard Mechanism FAQs. Retrieved from https://carbonmarketinstitute.org/app/uploads/2023/01/Safeguard-Mechanism-FAQs-June-2024.pdf

[10] Morton, A. (2018). Emissions increases approved by regulator may wipe out $260 million in Direct Action cuts. The Guardian 19 February 208. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/feb/19/emissions-increases-approved-by-regulator-may-wipe-out-260m-of-direct-action-cuts

[11] Kumarasiri, J., Jubb, C. and Houghton, K. (2016). Direct Action not as motivating as carbon tax say some of Australia’s biggest emitters. The Conversation, 2 September2016. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/direct-action-not-as-motivating-as-carbon-t…

[12] Macintosh, A. and Butler, D. (2023). The unsafe Safeguard Mechanism: how carbon credits could blow up Australia’s main climate policy. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/the-unsafe-safeguard-mechanism-how-carbon-credits-could-blow-up-australias-main-climate-policy-213874

[13] Australian Government. (2023). Climate Change Act 2022. Retrieved from:- https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2022A00037/latest/text

[14] The Australia Institute. (2021). Questionable integrity: Non-additionality in the Emissions Reduction Fund's Avoided Deforestation Method. Retrieved from: https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/questionable-integrity-non-additionality-in-the-emissions-reduction-funds-avoided-deforestation-method/

[15] Macintosh, A. and Butler, D. (2023). Op.cit.

[16] ibid.

[17] Australian Government. Clean Energy Regulator. (2024). Safeguard Mechanism. Retrieved from:- https://cer.gov.au/schemes/safeguard-mechanism

[18] Australian Government. Clean Energy Regulator. (2024). Managing excess emissions. Retrieved from: https://cer.gov.au/schemes/safeguard-mechanism/managing-excess-emissions

[19] The Australia Institute. (2022). 4.3 Billion Tonnes of Emissions is not OK. p8 Retrieved from: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Australia-Institute-submission-NWS-extension-proposal-WEB.pdf

[20] ibid,

[21] 21Mt pa CO2-e over twenty (20) year lifecycle. Vide The Australia Institute. (2023). Emissions from the Tamboran NT LNG Facility. p.4 Retrieved from: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Report-Emissions-from-the-Tamboran-NT-LNG-facility-WEB.pdf

[22] ibid. 60 21Mt pa CO2-e over twenty (20) year lifecycle.

[23] Climate Analytics. (2023). Emissions impossible: Unpacking CSIRO GISERA Beetaloo and Middle Arm fossil gas emissions estimates, Retrieved from: https://climateanalytics.org/publications/emissions-impossible

[24] vide Shine, R. (2024). Have WA’s new environmental protection laws left the state’s EPA a toothless tiger? ABC Analysis. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-10-20/wa-new-environmental-protection-…

[25] Climate Action Tracker. (2024). Highlighting the hypocrisy: fossil fuel export emissions. Retrieved from: https://climateactiontracker.org/blog/highlighting-the-hypocrisy-fossil-fuel-export-emissions/

[26] ibid.

[27] Macintosh, A. and Butler, D. (2023). Op.cit.

[28] Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water. (2023). Annual Climate Statement 2023. p.21 Retrieved from: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/strategies/annual-climate-change-statement-2023

[29] Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2024). National Inventory Report 2022. p.41 Retrieved from: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-inventory-report-2022-volume-1.pdf

[30] Morton, A. (2024). Let’s be honest: Australia’s claim to have cut climate pollution isn’t as good as it seems. The Guardian 4. September 2024. Retrieved from:- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/sep/04/australia-climate-change-pollution-renewables

[31] Australian Government. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2024) Australia’s emissions projections 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/publications/australias-emissi…

[32] Shine, R. (2024). Op.cit.

[33] Australian National Audit Office (2024). Issuing, Compliance and Contracting of Australian Carbon Credit Units. Retrieved from: https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/issuing-compliance-and-contracting-australian-carbon-credit-units

[34] Macintosh, A. and Butler, D. (2023). Op.cit.

[35] van der Woude, A.M., Peters, W., Joetzjer, E. et al. Temperature extremes of 2022 reduced carbon uptake by forests in Europe. Nat Commun 14, 6218 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41851-0

[36] Johnson, L., and Hortle, R., (2024) Measuring and reporting bushfire emissions, Tasmanian Policy Exchange, University of Tasmania. Retrieved from: https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1697841/Measuring-and-reporting-bushfire-emissions.pdf

[37] Environment Centre NT (2024). Climate Forum : In Conversation with Bill Hare. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/EicoUnJ0qWA?si=NsuKsPNlyPIGyPY2

[38] Morton, A. (2023). Methane emissions from Australian coal and gas could be 60% higher than estimated. The Guardian. 24 February 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/feb/23/methane-from-australian-coal-and-gas-could-be-60-higher-than-estimated?CMP=share_btn_url

[39] Cannane, S. (2021). How Satellites are challenging Australia’s official greenhouse gas emissions figures. Retrieved from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-12-03/satellites-are-challenging-australias-coal-mining-industry/100663676?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web

[40] CSIRO. GISERA (2024). About Us. Retrieved from: https://gisera.csiro.au/about/

[41] ibid.

[42] Climate Analytics. (2023). Emissions impossible. Unpacking CSIRO GISRA Beetaloo and Middle Arm fossil gas emissions estimates. p.6 Retrieved from: https://ca1-clm.edcdn.com/assets/emissions_impossible.pdf?v=1698659237

[43] ibid.

[44] The Australia Institute. (2024). LULUCF explained: Why Australia’s emissions aren’t actually going down. Retrieved from: https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/lulucf-explained-why-australias-…

[45] ibid.

[46] Grattan, M. (2024). Australia on track to meet 2030 43% emission’s reduction target, on latest figures. The Conversation. 26 November 2024. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/australia-on-track-to-meet-2030-43-emission…

[47] Commonwealth of Australia. Department of Climate Change Energy and Water. (2024). Quarterly Update of Australia’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory. June 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/publications/national-greenhou…

[48] Commonwealth of Australia. Department of Climate Change Energy and Water. (2024). Quarterly Update of Australia’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory. June 2024. Vide Data Table 1 A https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/nggi-quarterly-…

[49] ibid. Figure 3A.

[50] Environmental Defenders Office. (2023). Safeguard Mechanism Reforms- Another significant step in Australia’s climate law renaissance. Retrieved from: https://www.edo.org.au/2023/04/06/safeguard-mechanism-reforms-another-s…

Header photo: J.D. Irving Smoke Stacks, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada © 2015 Tony Webster. All rights reserved. Licensed under Creative Commons (cc-by-sa-2.0) [1]

[Opinions expressed are those of the author and not official policy of Greens WA]