2025-09-01

There is a long, varied and deep tradition of philosophical justification of peaceful disruptive protest action – which also resonates with thinking about how moral education should be developed in schools.

By Rob Delves, a member of the Green Issue Editorial Team.

A background story

About two years ago, Jo Vallentine, probably the WA Greens most enduring and ethical of protesters, invited two members of Grandparents for Climate Action – myself and Les Harrison (our leader, except we don’t have one!) to join her at the Northbridge Police Complex for a meeting with two senior police officers, who had agreed to an open-ended chat about various forms of climate protests in the city.

The hour-long discussion was overwhelmingly conducted respectfully and in the spirit of seeking to appreciate each other’s ethical position and responsibilities. We all easily agreed that violent behaviour, such as damaging property, but especially physical attacks on other people, was wrong. Jo was careful to explain that her bedrock commitment was to peaceful protest only and we GPs totally agreed with that.

There were only two interesting differences of opinion where the spirit of goodwill slipped several notches. Our meeting was very soon after the Disrupt Burrup Hub attempted action outside the home of Woodside’s CEO. In a moment of silence after a discussion on an issue, one police officer suddenly spoke out with some passion along the lines of “but when your protest targets someone’s home, that becomes a much more serious matter.”

He was obviously speaking from a strong personal ethical position, rather than the law, perhaps a strong belief about the sanctity of the home, which I admit has some resonance with Australians (though not to the extent that we will all campaign relentlessly to ensure everyone is provided with a decent, affordable, secure home to enjoy that sanctity – I was tempted to mention that, but tactical common sense prevailed, so I shut up on that issue dear to my Green heart).

Instead, I asked him to comment on the comparison between that recent DBH action and an incident several years ago where my front door was smashed open and several things stolen from the house, plus the contents of drawers and cupboards flung onto the floors. I suggested firstly that if the offender was found they would probably deserve a moderate fine or community service and secondly that this action was several degrees morally and legally more serious than merely holding a protest outside a home, and therefore the DBH crew should receive a much lower fine.

I said that if someone chained their neck to my (non-existent) front gate, I would be slightly bemused and ask them if they needed any help, for example, a cup of tea ‒ which I noted was probably not the most appropriate aid offering for someone whose neck was chained to a gate. This attempt at light heartednesses only angered the officer more and he argued fiercely that it was the decision to target anyone’s home that crossed the red line, not the actions at the home. Les always reads the emotions of a room much better than I do and from memory his foot was giving my ankle a decent workover at that point, so we agreed to change the subject.

The second strong difference of opinion involved disruption more broadly. The police struggled to understand why we felt so strongly about the importance of climate actions in all forms, so strongly that at times our protests were very disruptive to the general public, for example our attempts to occupy a roadway, bridge, entrance to a building, etc… It appears to me that there’s been a change in the last year or so – previously the red line was protest that wasn’t peaceful, whereas now it seems that you cross the red line when your protest “disrupts the right of the public to go about their everyday business.” It’s a serious hardening of the anti-protest laws and has motivated me to think much harder about whether the ethical basis of disruptive protest is strong enough to justify public inconvenience, and also strong enough to justify deliberately committing to breaking a law.

What follows is that ethical reasoning.

In praise of moral reasoning

In 1979-80 I was studying part-time for a postgrad degree in Curriculum Studies at London University and somehow became excited by, even obsessed with, one of the elective units – Moral Education. Like many teachers, I hadn’t thought about this as teaching ethics, but solely as developing strategies to create an orderly classroom (ironically one very intolerant of disruptive behaviour!). Just so that students could focus on learning – in other words, purely pragmatic, to allow effective teaching, not as a part of teaching ethical behaviour.

The unit made the case that moral education involves much more than achieving calmer classrooms – in fact, one of the priority goals of education should be raising good women and men. What does it mean to be a good person? Interestingly, the most persuasive answer is that a good person is not someone who has learned how to behave well, but rather a person who understands how to think through ethical issues to the highest level possible. In other words, moral education should aim to teach the highest forms of moral reasoning.

The famous Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget analysed how moral reasoning advanced as a child ages. However, in the 1960s, Lawrence Kohlberg, from the University of Chicago, took this idea further by proposing that ethical thinking advances through several stages of moral development. His theory holds that moral reasoning is a necessary condition for good ethical behaviour. For his studies, Kohlberg presented students with a series of ethical dilemmas and analysed the reasoning they used to justify their decisions, rather than the actual decisions they made.

He concluded that there are several stages of moral reasoning, each more adequate than their predecessor. The earliest stages focus on selfishness: how can I get the best deal for me (yeah, Trump is stuck around stage one, maybe two if we’re being generous). The next stages involve consideration of close ties to others. The individual believes that rules and laws maintain social order that is worth preserving.

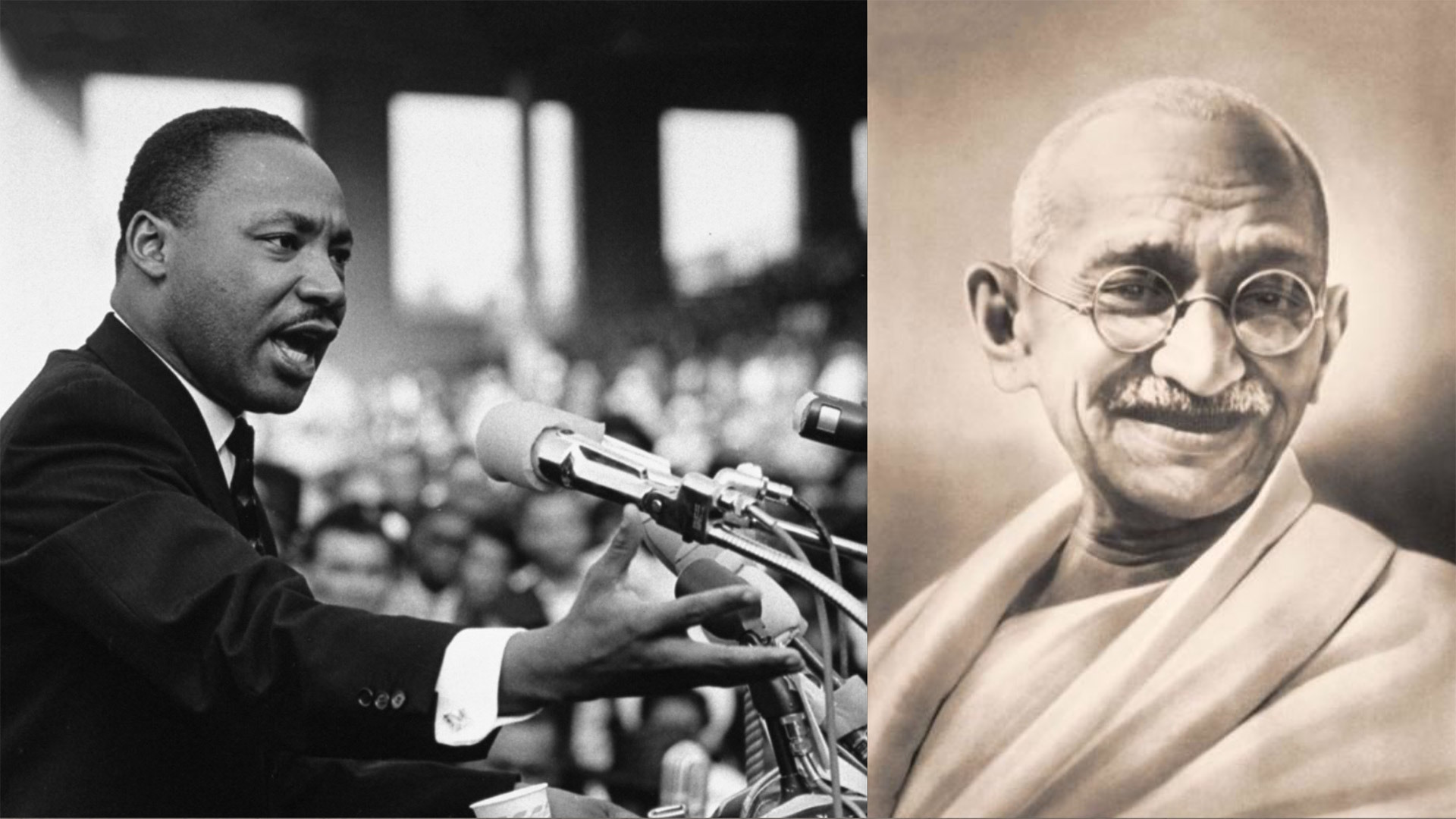

However, the highest stages involve an understanding of the social contract. People begin to ask, "What makes for a good society?" They begin to think seriously about the rights and values that a society ought to uphold. Kohlberg argued that there is a higher level of moral reasoning than always obeying the law and used the examples of Gandhi and Martin Luther King as exemplars of that higher reasoning.

For teachers, moral education should focus on helping students to advance to the highest levels of moral reasoning. In classroom discussions, I found that most students enjoyed the challenge of explaining how they reached their decisions about moral dilemmas. They agreed that it wasn’t ethical to always respect and obey the law, often referring to the moral wrong of supporting laws about slavery in America and Nazi rules about treatment of Jewish citizens. They appreciated the superior reasoning – and the courage involved – shown by those who opposed such laws. But also the more difficult reasoning involved in deciding how to respond to less extreme examples of unjust laws.

The ethical basis of civil disobedience

Where do climate rebels go for inspiration and a philosophical basis for the belief that peaceful civil disobedience is the highest order of moral reasoning? For many, Martin Luther King is top of the list. Like many others, he used jail time (in 1963, for opposing racial segregation) to think through the ethics. The result was his well-known Letter from a Birmingham Jail, whose main argument is that non-violent direct action is people’s right and duty in response to unjust, discriminatory and oppressive laws. He called on fellow ministers to join him in the tradition of the greatest Christian philosophers, especially Augustine, one of whose most quoted lines is “an unjust law is no law at all.” King also drew on the thinking of Thomas Aquinas. He defined an unjust law in two ways – any law not rooted in eternal and natural law and any law that degrades human personality. King rightly saw racial segregation in these terms.

Mahatma Gandhi, a man who knew the inside of jails very well, is also frequently admired for his courage and his absolute commitment to non-violence in his many protest actions. He certainly believed that there is a higher order of moral reasoning than total respect for the law. He justified his leadership of widespread civil disobedience against British colonialism by arguing that “non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as cooperation with good.”

Both would acknowledge the influence of the19th Century American activist Henry Thoreau. He did jail time for refusing to pay the part of his taxes that he calculated were going to support slavery and the invasion of Mexico. My favourite Thoreau story is his exchange with a friend who visited him and asked what the hell he was doing sitting in a prison cell – to which Thoreau replied by stating that the more important question was why his friend was not in there with him. A gently amusing nod at a lack of a moral compass.

I think Thoreau’s way of justifying direct action is the most direct line to student climate strikers and XR-style disruptive protesters. His basic argument is the question: what are the options open to us when the state no longer upholds our moral interests? His answer: civil disobedience.

King, Gandhi and Thoreau would recognise the debt they owe to the 17th Century British philosopher John Locke, widely regarded as the founding father of the principles of liberal democracy. Locke’s most famous concept is the Social Contract. Just as the power of any monarch is not absolute, nor is that of any government, even an elected one. Whatever powers a government holds are only granted by the people and are therefore contingent on it protecting people’s rights and ensuring these rights extend equally to all. It therefore follows that it is a citizen’s duty to oppose the state when it is not upholding those rights.

Locke also argued fiercely for an ethical commitment to peace and a “do no harm to anyone” philosophy. So, compared to King, Gandhi and Thoreau, Locke was perhaps more reluctant to support civil disobedience, but accepted that it was legitimate in extreme circumstances when all other avenues seeking redress had been exhausted. This is close to the heart of older climate campaigners who have beavered away for years patiently advocating for the science-based urgent action needed to address the climate crisis – and being ignored at every turn.

In taking disruptive climate action, we stand on the shoulders of the giants of Christian philosophers, leaders of other religions and the founder of liberal democratic principles.

Header photo: Arrests at an XR Grandparents protest. Credit: Nancy Miles-Tweedie

[Opinions expressed are those of the author and not official policy of Greens WA]