2025-07-03

Expensive weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic have only limited success in enabling obese people to maintain a healthier weight. Instead, our health policy should target junk foods, especially much tighter regulation of their advertising.

By Dr Peter Sprivulis, a member of Fremantle-Tangney Greens and a semi-retired emergency physician and digital health specialist.

Has anyone noticed folk disappearing lately? By this I mean formerly portly, huffing and blowing friends or family members dropping several clothing sizes and smirking when asked whether or not their weight loss is deliberate or due to an unfortunate illness, say…cancer?

This ‘disappearing’ epidemic isn’t due to serious illness in most instances. Rather, its origin is in the widespread uptake of Ozempic, Mounjaro and their kin; game-changing injectable drugs originally developed for diabetes but also privately prescribed ‘(i.e. not government subsidised) ever increasingly for weight loss.

The drugs certainly work. Weight loss of over 10% of starting body weight is commonplace. ‘Wonderdrug’ ‒ that oft overworked superlative ‒ is perhaps applicable to these glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist drugs given their impact on both diabetes management and obesity.

Not THAT wonderful

But Ozempic and friends are not without drawbacks. For one, not everyone is comfortable injecting themselves once a week. Demand has outstripped supply on occasion, resulting in intermittent access for diabetics, whose genuine need should be prioritised over and above mere weight loss users.

Unsubsidised prescriptions are expensive. Most Australians can’t afford the $300-400 a month cost of a private script, particularly on an ongoing basis. And then there is the issue of how long to remain on the weekly injections.

It is one thing to lose weight. Quite another to maintain weight loss without these expensive crutches. Most folk who stop the injections regain weight ‒ often regaining more fat than they lost and restore less muscle than they started with. Both outcomes are very bad for long term health.

Which leads to a health policy dilemma ‒ are we better to subsidise the GLP-1 agonist drugs and have half the Australian population on them forever (costing over $50 billion per annum) or are there more rational (and cheaper!) policies we can pursue to reduce the proportion of obese and overweight Australians; and in doing so, actually SAVE money on healthcare and improve quality of life.

We need to start thinking about such policies by asking why are so many of us fat and unhealthy in the first place? Australia has one of the fattest populations on earth. More than 60% of Australian adults are overweight. One in four Australian adults are obese. Australian children are amongst the fattest in the world with one in four overweight and nearly 10% obese.

The normalisation of eating junk

The fattening of Australia is closely correlated with two related trends in junk food eating:

1) Increasing regular consumption of fast food meals as substitutes for home cooked meals, which, due to their high energy and fat content, typically provide nearly half an adult’s daily energy requirements in just one meal.

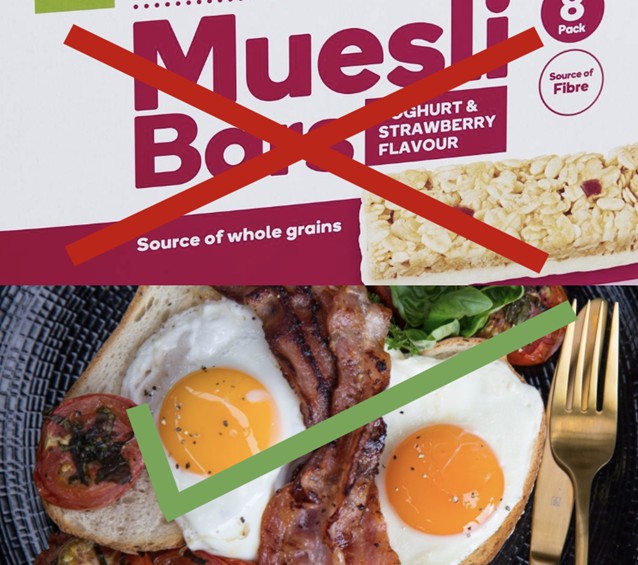

2) Increasing consumption of non-essential energy dense snack processed foods and beverages, such as soft drinks, sweetened dairy products, deep fried snack foods, sugary fruit products and muesli bars which have been normalised as substitutes for simple healthy foods such as water, milk and unprocessed fruit and vegetables.

Currently, over a third of Australian adult and child caloric intake is from junk food. Similar junk food consumption patterns are seen in many other countries. There is good evidence that junk food consumption is driven by junk food advertising, with companies like Coca Cola spending billions every year. Preschoolers believe junk food with cartoon characters on the pack taste better. Younger Australian kids are exposed to over 800 TV junk food adverts annually despite a voluntary code of practice against such advertising. Older children are exposed to more than 100 junk food ads per week via their smartphones. Junk food related obesity is relentlessly increasing across the globe, damaging the health of both developed and developing economy populations.

Here in Australia, the recent moves by the Federal Greens to pursue junk food broadcast media bans and South Australia’s banning of junk food advertising on public buses, trains and trams are to be applauded. Meanwhile our WA Labor government has left a similar advertising ban on our public infrastructure in limbo for half a decade. Perth kids are instead exposed to 70 junk food ads on school buses daily! Although public transport and publicly owned roadside billboard junk food advertising bans would be a good start, it is likely far more aggressive restrictions on such advertising will be needed to materially change what are now entrenched junk food consumption habits in Australia.

Beyond publicly owned advertising ‘vehicles’

We know from the fight with big tobacco that big corporations will, in response to any particular restriction on advertising, look to bolster any and all other channels they perceive as being effective. A particular gear grinder for me as a medico is the carpet bombing of junk food ads across major Australian sporting codes (e.g. MacDonald’s & AFL/Auskick, KFC’s bucket heads & Cricket’s Big Bash League). All of which aims to link junk food consumption with healthy activities (i.e. sport). There is no justification for allowing such advertising to continue. Another gear grinder – for no less than the WA Cancer Council – is point of sale promotions by supermarkets. But why stop at banning ‘promotions’? Walking down any supermarket aisle is an exercise in junk food advertising exposure.

Beyond mere point of sale promotions, could we not take additional leaves from the national Tobacco Control play book? Such as, only allowing plain packaging of food items clearly aimed at school lunchboxes, limiting added sugar or particularly sugary juices to fruit products and implementing impactful health warning messages on certain junk food products? Such changes are unlikely to harm the local fish and chip shop, who have made do with plain packaging for decades and don’t spend massively marketing their product as suitable for consumption three meals a day. The aim should be to denormalise everyday consumption of junk.

What about a (junk) food marketing tax?

Although governments around Australia can and do produce marketing messages promoting healthy eating, these messages are overwhelmed by ubiquitous and incessant junk food marketing. A marketing tax for particular types of unhealthy foods and alcohol was mooted for Australia in 2010, payable by the marketers of such food products. A rate of 100% (that is a dollar of tax payable for every dollar spent upon marketing on junk foods) would provide a direct, correlated source of funding for healthy eating and other health promotion messages. Such funding would allow more effective health promotion messaging across the same wide range of channels used by marketers of junk foods

A junk food marketing tax could also act as a disincentive to marketing expenditure and would likely increase the price of heavily promoted junk foods. Less marketing and higher prices might modestly impact junk food purchases and consumption. A marketing tax would be less regressive than a specific ‘sugary drinks’ sales tax, which would impact lower income earners disproportionately. Junk food marketers could choose to spend less on marketing their products less and pay less tax.

The public is ready

Surveys indicate the Australian public is already receptive to stronger junk food advertising restrictions, particularly restriction of advertising of junk food aimed at children. WA Greens public facing policies covering food, education and healthcare offer no public policy statements aimed specifically at tackling junk food marketing. In the absence of policies to combat the marketing and normalisation of junk food consumption, Australians will continue to get fatter, live sicker and die younger. Is it time to develop a junk food marketing policy given these high economic and personal costs?

[Opinions expressed are those of the author and not official policy of Greens WA]