2018-03-23

In 1996, ABS data showed that one in five Australian adults were close to illiterate. 20-odd years on, it doesn't appear things have improved – and it could be down to the politics clouding the way we teach our kids to read.

By Alison Clarke

In 2005, I co-convened the Victorian Greens state election campaign committee, and we chose Morgan Poll values segments to target with campaign messages. We did not choose the 'A Fairer Deal' segment, described by a campaign wag as the 'Yez can all get f***ed' segment. Here's how the Morgan Poll describes them:

Finding an escape, if only temporary, from their problems is a priority for people in the Fairer Deal Segment. Generally low-income earners, they feel they've got a rough deal out of life and tend to channel their frustration through loud motorbikes, hotted-up cars, beer and TV.

I grew up in Western Victoria's speedway country so have known a few YCAGFers, and can't write them off. Apart from concerns about equality, the impact of petrol-headism on our climate and the life expectancy of cyclists, I worry about their lack of literacy skills. Voters of this mindset contribute to the electoral success of the likes of the Shooters and Fishers, Pauline Hanson, Donald Trump and Brexit.

Literacy statistics

I'm a speech pathologist who works mainly with struggling readers and spellers. This makes me acutely aware that if you can't read or write in our complex, print-based society, your educational, health, employment, financial and other prospects are pretty much f***ed.

Back in political amateur hour, we Greens sometimes produced polysyllabic campaign materials. As an antidote, I'd bring my 1996 copy of the Australian Bureau of Statistics' adult literacy survey to meetings, and invite everyone to estimate the percentage of voters in each of its five literacy-skill categories.

Then I'd show them the data: nearly one in five adults were close to functionally illiterate. Only about a fifth were doing well, including a tiny two per cent with top-level skills. Everyone else had some level of difficulty using printed materials.

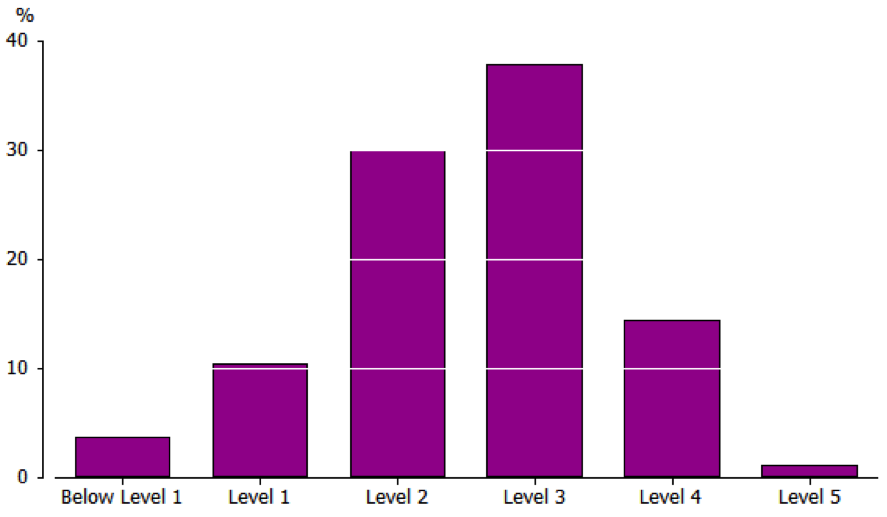

I'm still not sure why nobody rioted when these data first appeared, but 20 years on, surely things have improved? Alas, no. Here's a graph summarising the most recent (2011) data.

About 44 per cent of adults still have difficulty using many of the printed materials encountered in daily life (levels 1 or 2) and about 14 per cent have very poor skills. Fewer than one in five are managing well.

Literacy is widely considered a proxy for intelligence, so many people at Level 1 and below feel great shame and grow adept at hiding their difficulties. To them, dense, bureaucratic government publications like Centrelink forms must seem like an exquisite form of torture.

Statistics on literacy among kids are not much better. The 2016 Progress in Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) compared Year 4 pupils' reading skills around the world. Only 81 per cent of Australian children reached the 'proficient' benchmark. About seven per cent were reading 'very poorly', far too many of them Indigenous.

How many of them will join the next generation of YCAGFers? Our education system is failing them, mainly because of prevailing teaching methods.

Italian spelling is not horrible like English

An Italian colleague once told me there are no dyslexic Italians. “Italian spelling is not horrible like English,” she said. Like Finnish, the Italian language has (more or less) one letter per sound – so everyone learns to read accurately, though Italian dyslexics, who do exist, remain dysfluent.

Linking sounds and spellings in English takes about three times longer than it does in Italian or Finnish. Leaving aside linguists' arguments about how to slice and count sounds, for teaching purposes English has 44 sounds (24 consonants, 20 vowels) but 26 letters. Letters must thus work overtime in pairs like ch, sh and th, and vowel letters do multiple shifts in spellings like ai, ee, ea, ie, oa, oo.

We have three-letter combinations like igh in night and dge in fridge, and four-letter combinations like augh in naughty daughters. Most sounds have several spellings. Many sounds also share spellings (like the ou in out, soup, young and cough, and the y in yes, by, baby and gym).

This difficult, opaque spelling system can and must still be taught well. Linguists know what all the parts are and how they fit together. Scientists have been studying reading for decades. Unfortunately, this knowledge is not passed on reliably to teachers, who are as much victims in this scenario as struggling students, given the impact of student illiteracy on teacher workloads and job satisfaction.

The reading wars

The reading wars are long-running arguments in the English-speaking world about the best way to teach reading. The two sides used to be called 'whole language' and 'phonics'. For decades, the whole language approach has dominated in school education.

The central idea of this approach is that learning to read is like learning to speak, so if we just immerse children in written language they will naturally pick it up. Children are encouraged to rote-memorise and guess words from pictures and sentence context, and only sound them out as a last resort.

The dominance of this idea caused plummeting literacy levels around the English-speaking world. It is simply bunkum. Written language is a human invention – not an instinct like spoken language.

As more and more research highlighted the vital importance of phonemic awareness (awareness of the sounds in words) and phonics in early and remedial literacy teaching, whole language was given a swift sprinkling of token phonics and rebadged 'balanced literacy'.

However, in early-years classrooms around the country, teaching practices hardly changed. Most five year-olds are still given predictable texts containing spelling patterns they have never been taught, and encouraged to guess words from pictures, context and first letters, not sound words out.

Kids are still sent home with lists of high-frequency words to memorise by rote, and required to make personal collections of recently-misspelt words, then practice spelling them in pointless, ineffective ways (visual copying, reciting letter names, etc).

Schools still identify the one in five beginners whose literacy needs aren't being met by waiting to see who fails. Who can't do it. Who feels stupid. Who starts crying. Who doesn't want to come to school.

Balanced literacy advocates argue that everyone learns to read differently, so a mix of teaching methods is best. But in his book Reading in the Brain, neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene debunks this:

Every child is unique... but when it comes to reading, all have roughly the same brain that imposes the same constraints and the same learning sequence... Reading instruction … must aim to lay down an efficient neuronal hierarchy, so that a child can recognise letters and graphemes and easily turn them into speech sounds. All other essential aspects of the literate mind – the mastery of spelling, the richness of vocabulary, the nuances of meaning, and the pleasures of literature – depend on this crucial step. There is no point in describing the delights of reading to children if they are not provided with the means to get there.

As well as repeatedly confirming the educational superiority of an early focus on the relationship between sounds and letters, reading research has shown that when we learn to read, we create a new brain circuit linking our visual and speech systems. This in turn transforms how we listen and speak, and perhaps even how we think.

Unfortunately, many people whose politics are otherwise progressive work hard to maintain the mainstream balanced literacy approach. They downplay the importance of phonics, and oppose the introduction of UK-style phonics teaching and assessment in the early years, though the most recent PIRLS data indicate that the UK's weakest readers' skills are improving, and ours are not.

Teachers to the rescue?

The key linguistic areas that literacy teachers need to study are phonology (the speech sound system), orthography (spelling patterns and relationships) and morphology (word-building from smaller, meaningful parts e.g. auto + bio + graph + ic + al). Some etymology knowledge can also help with funny stuff like the w in two (pronounced in Old English, think twin, twice and twelve).

Good initial classroom teaching, plus intensive small-group work for strugglers in the first couple of years, should get most kids off to a good start. Only about three to five per cent of children should need further one-on-one intervention, and might end up with a diagnosis of dyslexia.

About 20 per cent of English-speaking children, and many more in disadvantaged groups, will always struggle to learn to read unless taught how to discriminate, blend and manipulate sounds in words, and match them with their main spelling patterns in a systematic, explicit and cumulative way.

Balanced literacy advocates argue that other kids do not need this strong focus on the tin tacks, but in The science of reading: a handbook researchers Catherine Snow and Connie Juell conclude that “attention to small units in early reading instruction is helpful for all children, harmful for none, and crucial for some”. In light of the evidence supporting their findings in the UK and the US, they say, it is “puzzling that there remains any conflict about methods for teaching initial reading”.

Literacy and access to the contest of ideas

Even if people with poor literacy skills, YCAGFers and others wanted to read newspapers like the Guardian, Age, Saturday Paper or New Matilda, they cannot. Taking the first sentence from an article in each of these publications, I used MS Word's Spellcheck Flesch Reading Ease feature to check how easy it was to read (100 = very easy; the lower the score, the harder the text). The scores I got were: the Guardian: 19.8, the Age: 32.4, the Saturday Paper: 22.4, and New Matilda: 24.2. Meanwhile, the Herald Sun scored 63.6.

If we want people to read more than the Herald Sun, we need less ideology in early literacy education and more explicit, systematic teaching about how our spelling system works.

The political problem: Framing phonics as right-wing

High-profile phonics advocates like Kevin Donnelly and people from the Centre for Independent Studies are readily identified as right-wing. This, plus anti-phonics statements from the likes of Mem Fox (who writes lovely children's books but seems to think that the plural of anecdote is data), and teacher organisations and unions, can lead many progressives to write off the phonics approach as nothing more than an element in the Right's back-to-basics, school-as-factory-producing-workers-for-the-capitalist-machine agenda.

This is a serious mistake. There are people of all political persuasions on 'team phonics'. Most (like me) are professionals or parents helping struggling learners. Thousands of angry (mostly) mums of struggling learners have formed groups on Facebook and started giving education ministers stick about the system letting their kids down, and demanding phonics testing and teaching.

WA Labor MP Alannah MacTiernan argued convincingly for phonics in a 2013 Australian article Postmodern claptrap rules in schools. The whole language approach, she wrote, is one “that particularly fails kids from lower socio-economic and Aboriginal backgrounds. It also appears to disadvantage boys”. This, although there is “overwhelming scientific support for the alternative approach of highly structured direct instruction of skills associated with decoding writing”, and that “transformation” can occur when brave teachers use the alternative methods against the “departmental orthodoxy”. It is time, she says, for the federal government to step in:

it is immoral to allow so many Australian children to be victims of a failed educational fad. We are … failing to teach these kids to read [and] we are destroying their confidence as learners. It is time for federal intervention [because] the states have shown an inability to address this problem. Securing our future as a clever country depends on it.

Sadly, the rest of the ALP seems to have ignored her article.

Professor Pamela Snow, Head of the School of Rural Health at La Trobe University, recently wrote that “giving up unhealthy ideas and practices in early years reading instruction is no less important as a public health issue than challenging unhealthy eating, or smoking”.

Mandy Nayton OAM, president of the Australian Federation of Specific Learning Difficulty NGOs (AUSPELD), said in a 2016 interview that “many children … struggle to read because they simply don't get enough of the kind of instruction that will allow them to read”.

Neither Snow nor Nayton have any political axe to grind. Both sat on the expert panel that recently advised the federal education minister to introduce a Year 1 Phonics Check, to help teachers to identify those who are struggling to sound out words.

Victorian Liberal leader Matthew Guy recently announced he would introduce this check if elected in November. The ALP's education minister has no such plans.

Let's work with teachers to prevent literacy failure

Where will the Greens stand in all this? I want us to stand with reading scientists and kids struggling most with our complex spelling code, and their advocates. However, this is difficult while key, otherwise-progressive teacher organisations and education academics actively resist change and defend the status quo.

We must have zero tolerance for the kind of teacher-bashing conservative phonics advocates sometimes employ, and point out that both kids and teachers are badly let down by the current system.

Better linguistics/phonics teacher training and resources are the key to ensuring all but a small number of kids learn to read and spell in their first three years of school. Very few should need extra specialist help from people like me.

Achieving this would be bad for my business, but right now I feel like a paramedic below a cliff kids keep falling over. Come on: let's build a fence.

The older kids with reading and spelling difficulties I see often have a sullen, YCAGF look on their faces. It's pretty hard to wipe that look off, even after they can read and spell reasonably well.

Let's do what we can to make sure our education system catches such kids before they fail. You never know, some of them might even end up reading the Guardian and voting Green.

Alison Clarke is a Melbourne Speech Pathologist and ESL teacher. She has been the Victorian Greens Party Coordinator (2006-2008), a Yarra City Councillor (2008-2012) and Mayor (2011), and Vice-President of Learning Difficulties Australia (2015-2016).