2019-07-29

In her review of Shoko Yoneyama’s recent book, WA Greens Co-convenor Chilla Bulbeck examines the concept of new animism, how it pertains to the current political landscape – and how, in amongst all the challenges of our time, hope springs eternal.

By Chilla Bulbeck

Review of Shoko Yoneyama’s (2019) Animism in Contemporary Japan: Voices for the Anthropocene from Post-Fukushima Japan; Routledge: Oxon and New York.

“March 2011 in Fukushima turned out to be a silent spring, the depth of which no one may ever know,” begins Shoko Yoneyama in an evocative mourning for damaged life. “Peach trees blossomed and horsetail shot up from the snow, but all were irradiated”. “Random genetic mutations began amongst tiny pale-grass-blue butterflies”, made visible as “abnormalities in their eyes, wings and antennas”.

The catastrophe of Fukushima occurred in the same year China surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest economy, marking the end of Japan’s period of ‘super-modernisation’.

The less well-known disaster of Minamata disease ushers in this period. The disease was officially ‘discovered’ in 1956, at the beginning of Japan’s post-war high economic growth period.

Writing in this period between Minamata and Fukushima are four Japanese intellectuals who challenge Japan’s materialist expansion through the intellectual lens and lived experience of ‘postmodern animism’ or ‘new animism’.

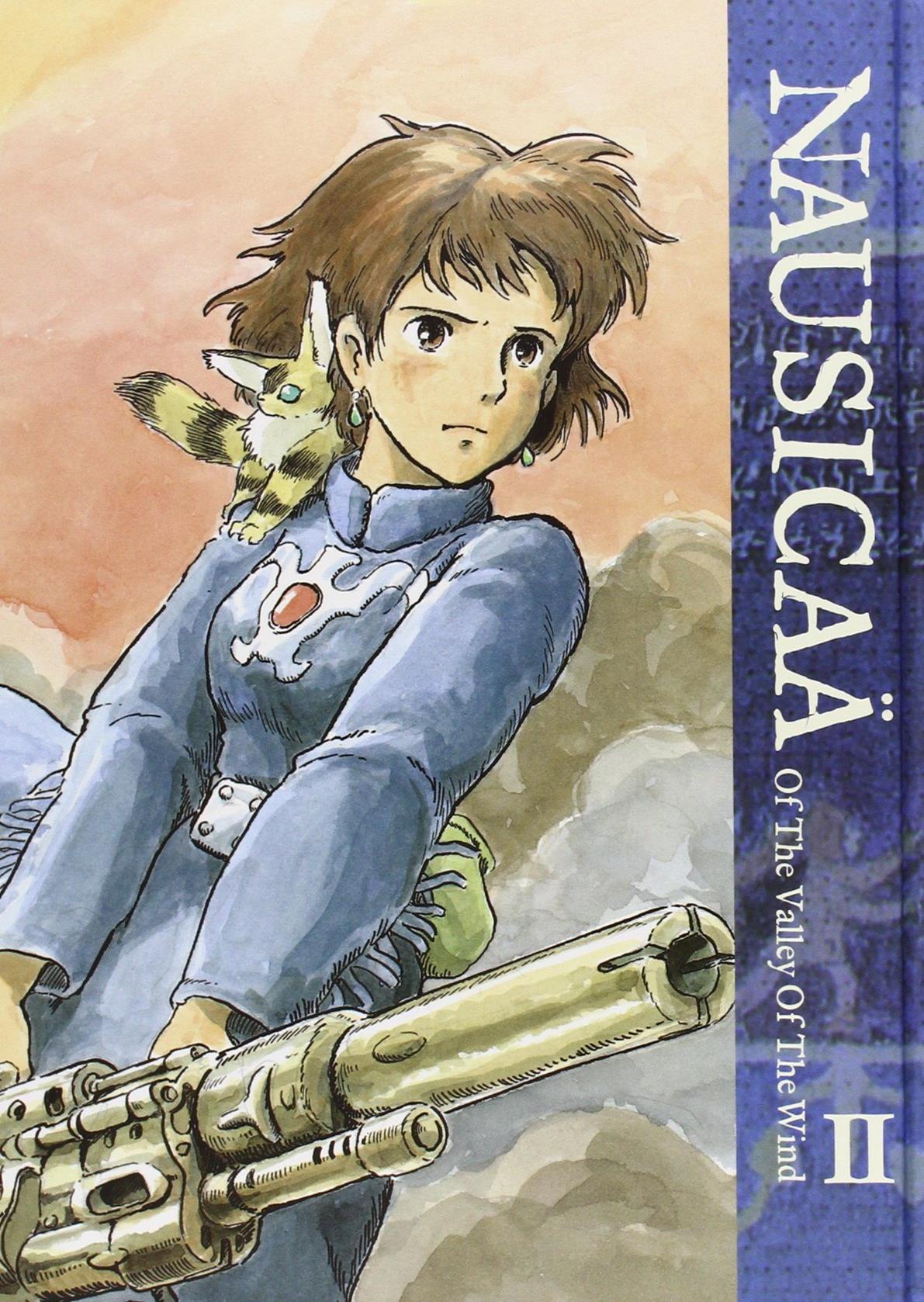

Fisherman Ogata Masato lost his family to Minamata disease, and wrestled with his response to this tragedy. Writing by environmental novelist Ishimure Michiko, described as the ‘Rachel Carson of Japan’, “connect(s) Minamata to society at large”. Tsurumi Kazuko delves into animism when the tragedy of the Minamata victims is beyond her sociological tool-box. From a critique of modernisation, national narratives and state Shintoism, she posits a theory of endogenous development based on ‘place consciousness’, its own ‘way of knowing’, honouring folk Shintoism and its spiritual connection to ‘little kami’ (spirits, deities). Animation director Miyazaki Hayao was inspired to make the anime film Nausicaä by the Minamata disaster.

A local connection

I read Yoneyama’s book in the shadow of our own disaster, the 2019 federal ‘climate emergency’ election. The result further entrenches the fault-lines dividing us: an increased vote for the Greens in the Senate, and also for white supremacist parties and more fossil fuel extraction, particularly in the lower house; a vote for income tax cuts to the wealthy but no increase in Newstart or abolishing robo-debts.

And after 18 May, Australia will hurtle faster towards our own silent spring: more Murray-Darling fish kills; more kaleidoscopic colours bleached from our battered reefs; more droughts, floods, fires and storms flattening crops, animals, humans.

Some Australians know this keenly, achingly, heart-breakingly. Many of us do not or will not know it. Many vulnerable Australians who stood to gain from Labor’s promised redistribution refused to hope or trust their fellow citizens and our broken democracy, voting with fear, anger and hatred to retain what little they had.

What should we do in this apocalypse?

Shoko Yoneyama argues we can no longer rely on the nation-state, on the grand narratives and abstract science of modernity, or the promise of happiness through material consumption. She offers instead ‘new animism’, taking the reader on an amazing and delightful journey through Japanese folk stories, local Shinto traditions, the living presence of slime mould, forests and the sea in the lives, and thus the imaginations and research of her protagonists.

Here, I will focus on the implications of forging our animistic connections in a world deformed by disasters like Minamata and Fukushima. Where pre-industrial animism was the taken-for-granted connection with the world, ‘new animism’ requires hard work by the self and is constructed in tension with post-industrial society. Self does the thinking and questioning which achieves the interconnectedness of three central concepts: life, nature and soul. Connection is key: Ogata talks of moyai, mooring boats together. Nature is around us, and also within us. The visible natural world is “a manifestation of the vitalistic force behind nature … life itself is a collective entity where there is no distinction between human and nonhuman, the animate and the inanimate”. Beyond our science-based understanding of ‘sustainable development’ or ‘interconnected ecosystems’ animism asserts the need for spiritual sustenance supporting our endeavours.

Further, because of the understanding that “the project of modernity is ill-conceived and dangerously performed”, new animism has a moral imperative. It requires us to learn “respectful relationships with other persons”, “not all of whom are humans”.

The Minamata story

The Minamata disease was caused by methyl-mercury effluent from the Chisso chemical factory, pouring untreated into Minamata Bay, disrupting the neurological pathways of first the fish, then the cats who ate the fish bones, and then the fishermen and their families in the nearby villages. Ogata Masato was initially committed to seeking compensation from Chisso for killing his family. Gradually, he came to realise that compensation is all about money, and silencing the victims, and that Chisso and the government had no care for the sufferers.

In a period of madness, Ogata finds the ‘Chisso within’ himself. He is part of the human world which is causing ecological crisis; he is consuming goods made from chemical factories; he might have a very different perspective had he been a Chisso employee. Ogata relinquished his long-held grudge against Chisso, and now understood the responsibility of humans towards other living things: “compensation does not mean anything to the sea. It means nothing to fish or cats” (p53). He recognises the tsumi (sin) he carries and must “apologise at the level of the soul” for what humans have done, thus finding “the salvation of his soul”. This means also meeting the souls of the deceased in dialogue, meeting other people without prejudice to convey the legacy of Minamata, connecting with future generations by keeping the embers of Minamata alive and regaining connectedness with the soul or life-world lost in modernity.

The villagers continued to eat the local fish even when the causal link with their strange disease was suspected. They continued to have children, even to grow up deformed, calling them ‘takara-go’ (treasure child) because they “placed complete faith in life and received it with reverence and gratitude”. “Ebisu, the god of the sea, was sharing this bounty” with them. The deity Ebisu is the ‘leech child’ of two kami, set adrift by those kami because deformed (limbless). Ebisu was found and cared for by humans and he reciprocated as the god of bountiful fortune in fishing and business.

Yoneyama explores Miyazaki Hayao’s philosophy through his manga (comic) version of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind¸ released two years ahead of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. The manga depicts “a post-apocalyptic future world” created by a nuclear war 1000 years earlier. Through Nausicaä’s interactions with giant insects (Ohmu), the Sea of Corruption (a deadly toxic forest) and the gigantic Slime Mould, Miyazaki refutes the dualism between good and evil (Nausicaä herself has darkness inside her) and between nature and human design. For example, Nausicaä has the opportunity to choose salvation through technology but rejects it because this promise of a ‘pure’ life comes only by “killing all (polluted) life”. Ultimately, Nausicaä’s “oneness with nature” enables her “to bring peace to the human world, even though it is a polluted world and even though the humans might still perish in the end”.

Embracing kehai

We are also compromised by the ‘sins’ of materialism. Our laptops “must have used nuclear-power-generated electricity at some stage in their conceptualisation, manufacturing, marketing, sales or transportation. … (W)e are all responsible … for the random genetic mutations amongst the tiny pale-grass-blue butterflies caused by the nuclear accident in Fukushima”.

Both ‘life-world’ and ‘system society’ (as Ogata describes contemporary post-industrial society) are, like two feet, indispensable for walking and we must learn to live with the dialogue between them, although “our pivotal foot should be in the life world”. Yoneyama calls on us to join like star sands the hotspots of thinking about animism, in our own unique “mandala-like space”, based on our own “fabric of relations”, our own grassroots locality and the whisperings, or kehai (hint of a movement) of “something out there”. Openness to the invisible and spiritual can reveal to us, perhaps only briefly, how beings of all kinds bring one another into existence.

In this necessarily deformed world, hope comes from the elm trees which were affected by abnormally hot weather one year but recovered the subsequent year which was just as hot, through “connecting to their ancient memories”, according to Miyazaki.

Hope comes from the revival of the Deer Dance when the drums which perform it are miraculously found in the rubble of the Fukushima disaster. Hope comes from the tiny undamaged shrines dotted along the “tsunami line” where the water divided and the tsunami ran out.

Instead of the government’s giant concrete seawall as a retort to future tsunamis, hope for the villagers and townspeople comes from building a living wall of tsunami debris topped by a Sacred Forest grown from local seeds and nuts.

Hope does not come from election outcomes. As Yoneyama notes, the massive anti-nuclear actions and demonstrations and their slogans of “life is more important than money!” did not translate into the ousting of the nationalistic bellicose Abe government or prevent the re-opening of nuclear reactors.

New animism recommends we breathe in the kehai, taking from it sustenance and meaning, and find our own local grassroots paths to connection and action, growing more effective as joining with others like star sands.

Chilla Bulbeck is the co-convenor of the Greens WA.

Shoko Yoneyama’s Animism in Contemporary Japan: Voices for the Anthropocene from Post-Fukushima Japan (2019) is available online or in stores as an e-book or hardcopy version.